Klyde Warren Park’s expanse of green has become the epicenter of new commercial and residential development, bridging the gap that once separated uptown, the arts district, and downtown.

At just five years old, Klyde Warren Park gets plenty of credit for the transformation that has occurred around its edges — new commercial and residential development, rising rents and property values, and a growing fan base that flocks to its myriad free events.

The park’s benefits are far-reaching: There’s the connectivity between downtown, Uptown, and the Arts District — a walkability that didn’t really exist in Dallas before the deck park was conceived and built. Klyde Warren’s green expanse of lawn and trees provides respite in a concrete jungle for nearby office and residential tenants.

“I don’t think anybody remotely realized the impact the park would have,” said Phil Puckett, who makes his living leasing office space in Uptown and downtown Dallas for CBRE. “It literally has become the epicenter of downtown/Uptown.”

One of the park’s biggest economic benefits has been its profound impact on commercial rental rates and property sales. Office rents skyrocketed in the first two years that park was open, rising between 30 percent and 60 percent, with the largest increases for those buildings immediately adjacent to the park, according to statistical data compiled by Puckett.

“Klyde Warren Park is really where the office market has shifted to from downtown,” Puckett said. “No one knew the impact and how great it would be.”

Today, office rental rates that were between $22 and $25 per square foot are about $40 per square foot, a 60 percent to 82 percent increase since opening day, he said. Puckett has long been compiling office lease data around the park. Looking at data from 2015, Puckett is able to show how triple net lease rates per square foot for 2000 McKinney and 2100 McKinney rose 56 percent and 64 percent, respectively, according to the Urban Land Institute.

Adjacent property, which was selling for about $150 a foot before the park came online, has more than doubled since it opened. Last year, 2000 McKinney St., a 21-story building that fronts Klyde Warren, sold for a record price of $200 million or $500 per square foot. Nearby, 17Seventeen at 1717 McKinney sold at a similar per-square-foot price.

The residential market near Klyde Warren is also booming. Back in the mid-1990s, the total property value of the area now known as Uptown was only about $500 million. Today, it has ballooned to about $5.1 billion, according to Uptown Dallas Inc.

The residential population in Uptown also has risen significantly, up by more than 50 percent between 2010 and 2016. A second-quarter 2017 report by CBRE notes that the Uptown/Oaklawn/Highland Park market now has 30,000 multifamily units with the highest rents in the region: $1.75 per square foot.

HOW THE PARK CAME TO BE

John Zogg, managing director of Crescent Real Estate Equities, recalls how Uptown was beginning to flourish in the early 2000s with growth in the Arts District, while downtown was struggling.

“I was working on a lot of downtown initiatives with (Belo’s) Robert Decherd in what was called the ‘Inside the Loop’ committee to revitalize downtown,” Zogg said. He recalled how he and Crescent owner John Goff were hosting investors in the Trammell Crow Center one day when the Nasher was under construction and American Airlines Center was completed. “They said, ‘You have great assets but what a shame they are so disconnected.’ After the meeting, John and I were looking down from the 42nd floor and wondering, ‘How do we solve that?’ Woodall Rodgers was the moat that disconnected everything.”

From that off-the-cuff conversation came the idea of putting a park over the freeway, Zogg said. (See the Klyde Warren Park Timeline on Page 63.) Crescent hired architect James Burnett to do an initial site plan of what might be possible and hosted a party, inviting property owners and others they thought might be interested.

Linda Owen, then president of The Real Estate Council, also was an instrumental cog in getting the park off the ground. TREC decided to provide $1.5 million in seed money to explore the feasibility of a deck park which got the project rolling.

Jody Grant, then head of Texas Capital Bank, said he learned of The Real Estate Council’s decision and reached out to Zogg with an offer to help lead a private fundraising effort for the park.

Grant would become an early donor, giving a $1 million personal commitment from himself and his wife, Sheila, and another $1 million from the bank, and would go on to lead the private fundraising efforts.

Initial funding led to city, state, federal, and private funding, as well as the creation of the Woodall Rodgers Park Foundation with Zogg, Grant, and The Real Estate Council’s Owen as the founding members.

BECOMING A CATALYST

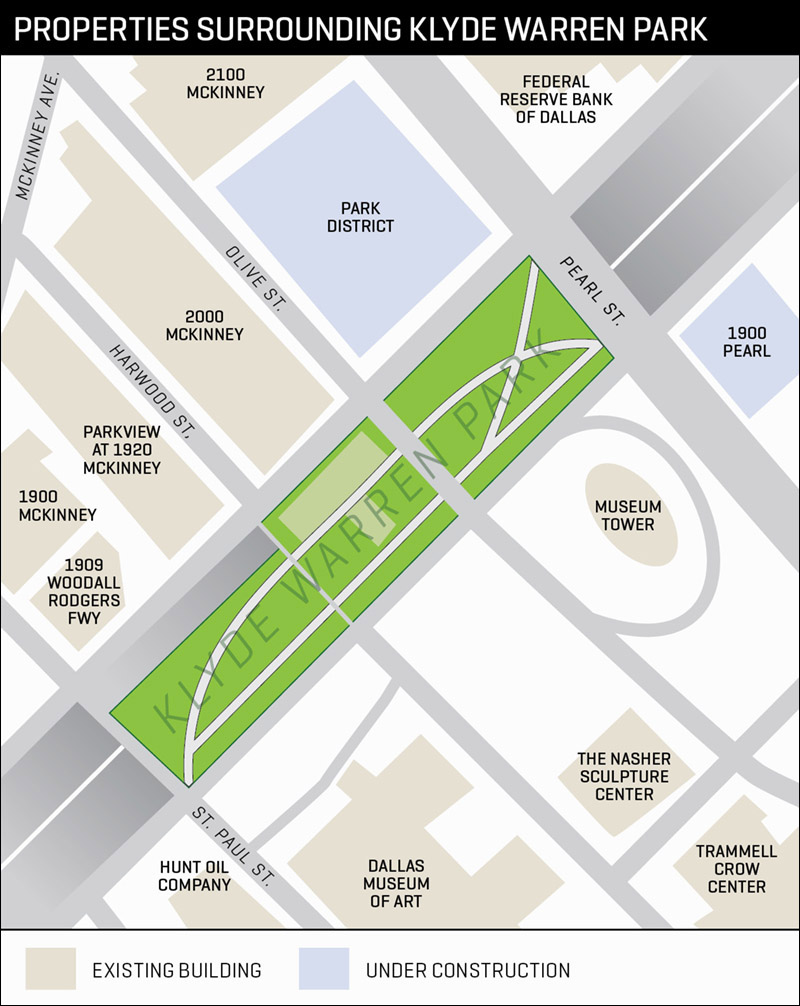

The 5.2-acre park has had a strong impact on the commercial real estate sector since its October 2012 debut, including four new adjacent projects: 1900 Pearl, which is expected to open soon; Park District, which is under construction; 2000 McKinney; and 1717 McKinney. Real estate experts say the higher rates that landlords are able to command near the park have enabled development to occur despite rising construction and labor costs, which might have otherwise stymied such projects.

Also nearby is Parkview at 1920 McKinney, a two-story, mixed-use, property, which was renamed last year to focus on its proximity to the park and RED Development’s Union mixed-use project at Akard Street and Cedar Springs Road, which is scheduled to open next year.

Construction recently began on HALL Art’s second phase, a 183-room boutique hotel, and 44 luxury high-rise condominiums. HALL Arts completed its first phase in 2015 with the opening of KPMG Plaza at HALL Arts and an adjacent half-acre park. Though the development is a block away from Klyde Warren Park, it is experiencing the benefits of being both in the Arts District and close to the park, said Kim Butler, director of leasing for HALL Group.

“The Arts District has been there for much longer than the park, but the park has helped activate the district and brings more pedestrians to the Arts District,” making the area more desirable from a development standpoint, she said.

“What it does most effectively is knit together Uptown and the Arts District such that it has benefited both districts in the growth in property values,” Butler said.

Lucy Burns, a partner with Billingsley Co., agreed, saying the park has had a positive impact on One Arts Plaza, 1722 Routh St., which opened in 2007.

“The activity it’s created has given increased life and attention to the Arts District,” she said. “When people are coming down to the park, the probability that they might go to the DMA (Dallas Museum of Art) or the Nasher or one of these other places is a lot higher.”

STRONG DEMAND FOR PARKSIDE PROPERTY

New buildings directly on the park have had strong leasing demand, said Bret Bunnett, executive managing director at Cushman & Wakefield.

“2000 McKinney and 1717 McKinney are 97 percent leased, and we expect that 1900 Pearl and Park District will be fully leased in the very near future,” he said.

Park District, a partnership between Trammell Crow and MetLife, is the largest project underway directly adjacent to Klyde Warren. It consists of a 20-story, 500,000-square-foot office tower facing Pearl, and a 34-story apartment building facing Olive with about 21,000 square feet of retail. Completion on the office tower is expected in late 2017 and the residential component in early 2018.

“The park is an incredible amenity to have on your front door,” said Scott Krikorian, senior managing director and principal at Trammell Crow.

Law firms, real estate companies, financial institutions, architectural firms, and others pursuing top-tier talent and the retention of professionals desire to be in highly compelling locations and well-amenitized buildings such as those being built adjacent to the park, and are among the industry sectors that have sought out space near the park.

A SPARK FOR DOWNTOWN

The park has produced a spark for downtown Dallas, spurring a variety of renovation projects beyond its edges such as the major redo underway at Fountain Place. “We see Klyde Warren as important for a number of reasons: one is the physical connectivity it brings, blending two areas of our urban core — the Arts District and Uptown,” said Kourtny Garrett, president and CEO of Downtown Dallas Inc. “As we think through our strategic planning processes … we are moving toward an ability to better connect downtown and all of our urban neighborhoods.”

Klyde Warren Park’s draw of over 1 million people a year is creating a huge impact in the urban core, she said.

“It opened when we were still working toward an awareness to help people understand all there is to do and see [downtown]. Klyde Warren reached a much wider circle of people to come experience the park and see all the other improvements happening,” Garrett said. “It continues to do that.”

Real estate and development experts said the park has become a development epicenter of sorts and will continue to be one in the future.

“These [properties near Klyde Warren Park] have become, probably, the most desirable properties in all of Dallas-Fort Worth, and one thing we were missing was a signature park,” Hall’s Butler said. “Having that, along with the Arts District, has matured Dallas as a city.”

And the development isn’t over, although land is certainly more scarce for building. The Miyama family of Japan owns two properties adjacent to the park: a low-rise office building and a motor bank, both fronting the park at St. Paul. They haven’t yet disclosed their plans for the property.

Ross Perot Jr.’s Hillwood also owns property at Field and Woodall and says it isn’t in any hurry to develop it.

“The unification of Uptown and Downtown through Klyde Warren has made that beachfront property,” said Ken Reese, executive vice president of Hillwood Urban. “We see this as a gateway site for people coming into downtown.”

The site allows for as much as 1.5 million square feet and could eventually bring a new skyscraper that alters Dallas’s skyline.

About a year ago, Hillwood held a “design charrette” with world-class architects to understand what might be possible. British architect Sir Norman Foster designed a circular high-rise of more than 70 stories to conceptualize what could be done at the site. Reese said that there are no plans at this time to build that kind of iconic, signature building, unless there’s a demand for it. But he believes such demand could exist at some future date.

“We think it could be a significant building for the city but we’d only do something like that if we had a large tenant in hand that had that kind of vision,” Reese said. “Klyde Warren has now set the stage for what is expected in terms of quality office product in Uptown/downtown: great space, the connection to green space, the food, the activation, all of those things that Klyde Warren provides is the new benchmark.”

KLYDE WARREN PARK TIMELINE:

The concept for building over Woodall Rodgers Freeway was first considered in 1968 when Vincent Ponte, an urban planning consultant hired by the city of Dallas to advise on the freeway, advanced the idea. The idea resurfaced in 1996. That’s when Kevin Sloan, a Dallas-based urban planner and landscape architect, is believed to have suggested a park over the freeway. Sloan’s idea, called Dallas Esplanade, was embraced by Gail Thomas and Louise Cowan at the Dallas Institute of Humanities and shown to city leaders, including the group developing what is now the AT&T Performing Arts Center. Below is a timeline of events once the idea took off.

- 2002: John Zogg of Crescent Real Estate Equities holds informal meetings and rallies support in the business community. Crescent Realty funds an initial site plan by landscape architect James Burnett. (Around this time period, the “Inside the Loop” committee also raised the idea of a deck park but instead pursued other park sites.)

- 2004: The Real Estate Council, via an effort led by then TREC President Linda Owen, provided $1.5 million seed money to kick off funding of a feasibility study.

- 2005: Jody and Sheila Grant provide a $1 million private donation and a $1 million donation from Texas Capital Bank.

- 2005: Grant, Zogg, and Linda Owen form The Woodall Rodgers Park Foundation, the organization that led the project from design to completion and currently oversees the park’s operations on the city’s behalf.

- 2006: The city of Dallas allocates $20 million in bond funding to help build the park. The park also receives $20 million from the state, $17 million from the federal government, and $55 million in private donations.

- 2007: The city and foundation sign a formal development-and-use agreement, setting out that the park will be owned by the city, while being privately managed and funded.

- 2009: Construction begins.

- Feb. 2012: Dallas billionaire Kelcy Warren donates an estimated $10 million to the park and names it for his then-9-year-old son, Klyde.

- Oct. 27, 2012: Klyde Warren Park officially opens.

- 2014: The park wins the prestigious Urban Land Institute Open Space Award and receives LEED Gold certification for its sustainable design and construction — two of multiple honors and awards received.

- Nov. 7, 2017: A city bond election will take place, which includes partial funding for a private-public effort to expand the park.

Timeline sources: Klydewarrenpark.org, D Magazine, Dallas Morning News, John Zogg