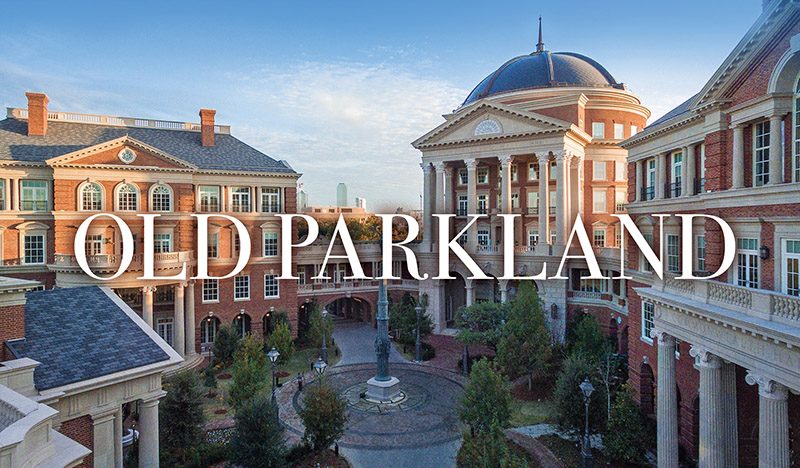

Go behind the gates of Old Parkland, where Harlan Crow transformed a historic hospital into one of the most stunning and exclusive office parks in Dallas.

Dallas is a familiar setting for many rags-to-riches stories of wildcatters forging their own fortunes. It’s also home to several business dynasties, led by people with last names like Perot, Hunt, and Bass—who traditionally have passed ownership of companies down from generation to generation.

An exemplary marriage of these two phenomena is Harlan Crow, the third son of Margaret Doggett Crow and commercial developer Trammell Crow. For this particular family, real estate is seemingly in their blood. Trammell’s father, Jefferson Crow, kept books for Collett Munger, who built Munger Place and was one of Dallas’ earliest commercial real estate tycoons. Trammell worked with the Stemmons brothers to repurpose the Trinity River floodplain by developing warehouses in what would become the Dallas Design District. He was named the largest American private real estate developer by Forbes in 1971. Of Trammell and Margaret’s six children, four were bitten by the real estate bug. Their only daughter, Lucy Crow Billingsley, and sons, Robert, Harlan, and Trammell S., each worked for various segments of their father’s business throughout the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s.

Billingsley launched her own company in 1996 with her business partner and husband, Henry, to develop land north of Dallas into International Business Park. Trammell S. primarily focuses on Earth Day Dallas and oversees the Trammell & Margaret Crow Collection of Asian Art. Harlan worked as an industrial leasing agent for Trammell Crow’s Houston outfit in the ’70s, then managed Dallas office building development for the company until the mid-1980s. He worked for Wyndham Hotels, which his father founded in 1981, for two years before taking the helm of Trammell Crow Interests in 1988.

For the next two decades, Harlan Crow ushered his father’s company into its next iteration, Crow Holdings, and became its chairman and CEO. He was involved in the IPO for the Wyndham Hotel Co. in 1996 and the IPO for Trammell Crow Co. in 1997. Today, Crow Holdings Capital-Real Estate manages private equity real estate funds for institutional investors (domestic and foreign) and is investing in the $1.8 billion of capital raised for Fund VII. Crow Holdings Development businesses, Trammell Crow Residential and Crow Holdings Industrial develop apartments and warehouses in major markets around the country. And Crow Holdings Capital-Investment Partners invests in a variety of asset classes on behalf of the Crow family and partner families.

After all that action in the early 2000s, Harlan was ready for a different kind of project. Back in 1987, the city had designated the Old Parkland hospital at Maple and Oak Lawn Avenues a Dallas Historic Landmark. The county repurchased it in 1996 with plans for redevelopment, but the complex sat vacant for years. The historic hospital went back on the market in 2005.

Harlan, a history buff whose personal collection includes original documents by American revolutionaries and famous neoclassical and impressionist paintings, partnered with Alliance Residential, which sought to develop a multifamily project on the 8.3-acre site. In 2006, they came in with a $16.5 million winning bid. Harlan thought Old Parkland would be perfect for a new Crow Holdings headquarters, so he quickly made an offer to buy out Alliance, thus sparking one of the most stunning redevelopments Dallas has ever seen.

UNEARTHING A BEAUTY

When Crow Holdings began construction on Old Parkland, it was a dilapidated dump. Crumbling walls and ceilings were covered with graffiti and signs of people who occupied the space while it was vacant, and the decades of inattention the property had experienced were obvious. None of this hampered Harlan’s vision, though; he wanted to create a corporate office park reminiscent of a college campus, where tenants could enjoy winding pathways flanked with sculptures and lined by majestic, shady trees, plus a slew of top-notch amenities.

He called on Dallas-based architecture firm Good Fulton & Farrell, a team that could pay mind to the project’s historical significance. The “new” Old Parkland was built in 1913, replacing a wooden structure that had been constructed in 1894. The classical, revival-style brick building with Georgian influences included a two-story porch that passers-by would come to remember. When Crow began restoring it in 2008, he maintained the entire front of the structure as it stood in the early 1900s. (A modern wall of steel-and-glass windows was added to the back.)

Part of the second floor was removed to expand the first-floor lobby, whose centerpiece is a glass encasement of pictures and memorabilia from the hospital that have been donated by people who played some part in Old Parkland’s robust history. The bulk of the first floor houses real estate professionals in the same open-office style that Trammell Crow pioneered.

Cathy Golden, the general manager of Old Parkland, has worked for Crow Holdings since 2013. “When Harlan first came to me, he said, ‘I know I can build buildings, and I know I can fill them up with people. I want Old Parkland to be more than just another office building full of people; I want it to be a place where there are conversations, there’s sharing of ideas, and there are thought leaders,’” Golden recalls. “What really has made this unique is, with all of the programs that we have—speakers, authors—it does stimulate a conversation. We invite tenants to most of those things, and whether it’s an event or just around the bar or at lunch, we’re seeing tenants having lunch or a drink with another tenant they didn’t know before they came here. It’s creating that synergy.”

In 2009, Harlan unveiled the renovated Nurse’s Quarters, a 23,000-square-foot building originally constructed in 1922 to serve as permanent housing for nursing trainees at Parkland Hospital. It’s aesthetically similar to Old Main and houses the majestic Pecan Room. Part elegant dining room and part stately conference hall, the Pecan Room has myriad historic artifacts. Behind its grandiose fireplace are planks signed by visiting luminaries.

There’s also The Tavern, which has a stained glass ceiling and outdoor terrace and was a favorite meeting place among tenants, prior to the opening of the Gren Door Restaurant and Bar. On the second floor, there’s a dining room and a conference facility; the third and fourth floors are office space.

Woodlawn Hall, the first new Class A construction on the campus, was also completed in 2009. You can’t really tell the 33,000-square-foot office building apart from the old-school buildings, though. Even sitting right next door to Old Main and the Nurse’s Quarters, Woodlawn Hall is a convincing reproduction.

The next campus addition, the 47,000-square-foot Reagan Place, was completed in 2011. Its Jeffersonian architecture was a small step away from the Georgian Revival style for Good Fulton & Farrell and Dalgliesh Gilpin Paxton Architects. It was the latter of two new buildings erected to “complement the original and historic landmark structures,” and it boasts a two-story balcony and a two-story rotunda with a stone portico. Like Old Parkland’s front façade, it, too, might become a recognizable local landmark.

Completing the far east side of the campus is Maple Hall, which was opened in 2013 and serves as the headquarters for TRT Holdings, the parent company of Omni Hotels and Gold’s Gym that relocated to Old Parkland from Irving. Designed by HKS and built by Brasfield & Gorrie, the six-story building offers 164,000 square feet of office space.

A 10-year tax abatement on 90 percent of the real property improvement value resulting from its construction, plus a $200,000 economic development incentive grant played an important role in the development of the property. When plans for Maple Hall were announced, the city of Dallas concluded the development would have a positive impact with property taxes and jobs.

EVEN MORE OF A GOOD THING

Buoyed by the success of his redevelopment efforts, Harlan Crow was ready to head west. Two four-story “sister buildings,” the 34,000-square-foot Commonwealth Hall and the 40,000-square-foot Oak Lawn Hall, were built in 2015 to flank the landmark Parkland Hall, whose shiny copper dome you might have seen from the Dallas North Tollway or Interstate 35-E.

Both of the sister buildings were designed by The Beck Group and Dalgliesh Gilpin Paxton Architects, and each features a historic statue at its entrance—Alexander Hamilton stands at the entry of Commonwealth, while Benjamin Franklin flanks the entrance of Oak Lawn Hall—plus underground conference rooms.

The copper-topped Parkland Hall is truly the statement piece of the property. Its Jeffersonian-inspired architecture is modeled after the Rotunda at the University of Virginia. The first-floor lobby has a marble fireplace, crystal chandeliers, and George Washington to greet entrants. Also designed by The Beck Group and Dalgliesh Gilpin Paxton Architects, it was finished in 2015. The six-story, 87,000-square-foot marvel offers views of downtown Dallas—and two rooftop terraces. Parkland Hall also offers two private restaurants, including The Green Dragon.

“There was a Green Dragon pub in Boston, and it was where the revolutionaries hung out,” explains Golden. “It’s from where Paul Revere rode and said, ‘The British are coming!’”

The last piece of the Old Parkland puzzle, The Pavilion, was also completed in 2015. It pays homage to Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s famous home. The stately first-floor public space has an impressive art collection on display underneath the towering glass dome, and its spiral staircase ushers guests down to the Century Hall and Debate Chamber—a work of art in its own right. The underground, oval chamber can hold up to 150 and has already served as a venue to collegiate and high-school debates, internal meetings, discussion on politics and policy, and other speaking engagements.

Crow Holdings says the chamber was “designed to facilitate debate and dialogue,” and the busts and quotes of Classical Greek and Roman philosophers are there for inspiration. “It hearkens back to ancient Rome and Greece and the Classical era, and ties it all together,” Golden says.

THE GREAT ESCAPE

When you stroll through the landscaped paths that meander between the monolithic buildings of Old Parkland, it’s easy to forget that you’re in the middle of one of the nation’s biggest cities, perched right next to bustling highways.

There are quotes and pieces of art embedded into the ground. In even the most unassuming of places, there’s a bust or a sculpture or an artifact to catch your eye.

“All of the bricks in all of the buildings are hand-molded, just as they would’ve been in 1776,” Golden says. “It was really an effort to inspire people, and a lot of people have asked if we have a walking guide, or an app, or a live guide. We’re considering that, just because I think there are a lot of people who would find it interesting. … But it was really intended for our tenants on our campus to kind of stumble upon stuff.”

And when your tenants are real estate investment groups, private equity firms, charitable foundations, and hedge funds, it’s not hard to get users of your property to pony up the extra rent money for additional amenities. But for some tenants, history has also played an important role in their decision to office on the campus.

“Southwestern Medical is a tenant here, and Southwestern Medical School started on this campus, so they tell me, in that spot,” Golden says. “It’s really interesting because, for rental rates, we were by far at the top of the market when we first started, and we really didn’t have trouble filling it up. People really get the value of being here because it’s a different deal; it’s not just an office, and we have incredible retention, and there’s just not a lot of turnover.”

At Old Parkland, which cost more than $200 million to build, rents hover around $60 per square foot. That’s significantly more than the Dallas average, but it’s the going price for on-site amenities like 24-hour security that uses closed-circuit TV surveillance, a 3/4-mile walking trail, a full basketball court, squash court, a fitness center, and plenty of oak tree-shaded land.

And for all of those perks, the property has been hotter than hot. “For the most part there’s been more interest than we can accommodate,” Golden says. “It’s a very fortunate place to be.”

The development has also piqued the interest of real estate investment groups from all over. As it seems, Old Parkland could set an enviable new standard for developers in North Texas and beyond.

Despite its size and prestige, Old Parkland is a very comfortable place to be. Porches on all of the buildings offer welcoming rocking chairs. There’s an old-fashioned barbershop where tenants can get a haircut.

Tenants have access to The Commons Café and The Green Dragon, an outdoor fireplace, and many venues for business and social gatherings. You can even get a massage in the fitness center, play squash, play basketball, get your shoes shined, or have your laundry washed and folded.

“I sat in on construction meetings each week and looked at this as it went along on paper and in planning, and you just can’t imagine it until it really goes vertical,” Golden says from the windy rooftop terrace of Parkland Hall. “To think about the scale of these buildings in such a tight space but still having the green space and the courtyard—it really has been a special project.”

It’s the art and artifacts that really set Old Parkland apart. There is so much to be seen, in fact, that Harlan conceptualized an essential highlight reel of the most noteworthy items, called “The American Experiment.”

Named for a term used by other countries during the late 18th century after Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence in defiance of Great Britain, “The American Experiment” at Old Parkland is comprised of more than 30 architectural elements, sculptures, and quotes etched into walls and buildings. And although some components are historic or excavated, others were commissioned.

One such piece, Alexander Stoddart’s “Eos Column,” serves as the central structure in the courtyard of West Campus. The bronze structure stands 45 feet tall and is topped with Eos, the winged goddess of dawn, and at its midpoint includes 4-foot tall depictions of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison next to John Locke and Adam Smith, figures from the Enlightenment. Their quotations are carved into the sculpture’s granite base.

Thomas Jefferson once said to John Adams at Monticello that he liked the dreams of the future better than the history of the past. Harlan Crow has seemingly unified the two at Old Parkland, creating an office campus and living landmark where, just as he dreamed it, people can gather to comfortably discuss the issues of the age and ideas for the future.