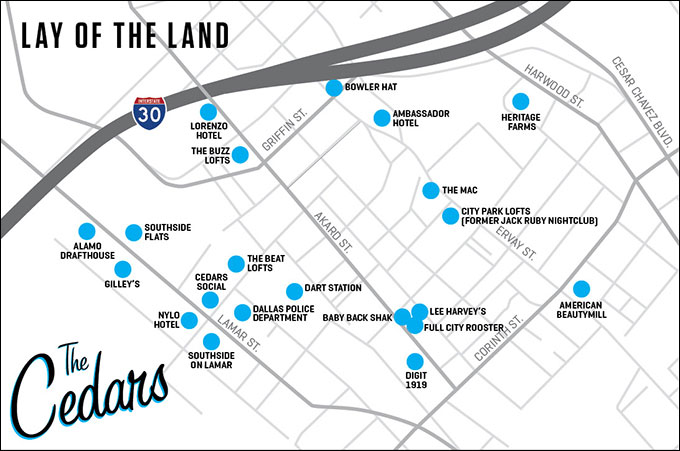

With a history dating back to the 19th century, The Cedars section south of Downtown Dallas was the home of stately mansions and cedar tree-lined streets. It has been reshaped into a place where loft living mixes with the Dallas Police headquarters and an influx of new businesses.

Bennett Miller is gone now but the Dallas urban pioneer — who bristled at being called a real estate developer — was the first to reimagine buildings in The Cedars when most people were avoiding this neighborhood situated on the southern fringe of downtown Dallas.

It was the early 1980s, and Miller bought several old buildings that he would convert into edgy urban lofts, starting a movement that would eventually gain steam and return Dallas’ oldest neighborhood to some of the vibrancy it enjoyed in its heyday. Today, the speed of development in The Cedars continues to increase as new development begets more.

In the 19th century, The Cedars was an enclave of stately Victorian homes and cottages for entrepreneurs, wealthy business leaders, and the city’s Jewish population, but as the years passed, it entered a period of decline. By the 1980s, The Cedars had become a blighted, gritty part of town that had transitioned from residential to heavy commercial and industrial uses. People avoided it.

Increased homelessness and crime plagued the area, but Miller saw its potential. He envisioned new uses for old buildings and saw the opportunity they presented to affordably house people near downtown. One of his most iconic developments was the transformation of the old American Beauty Mill flour plant into apartments offering dramatic views of the Dallas skyline.

EARLY ADOPTERS AND ADVOCATES

Phillip Robinson, president of The Cedars Neighborhood Association (CNA), moved into one of Miller’s renovated loft-style apartment buildings in the 1990s and soon became passionate about The Cedars and its future.

“I was fortunate enough to be renting one of his loft apartments in Jack Ruby’s old building,” Robinson says. “In 2005, [Miller] built the first new construction this neighborhood had seen in 60 years — a row of townhouses, and I bought the first one.”

Miller believed ownership was an important element for neighborhood stability and revitalization. Property owners, not renters, have a vested stake in the future health of a neighborhood.

As residential ownership began to increase in The Cedars, new owners began to advocate for their part of town — an area they felt had been neglected by the city. Neighborhood advocates such as Robinson arose to demand treatment on par with other areas concerning issues such as garbage pickup, access to recycling bins, code enforcement, and crime control.

“Once these homes were built, we realized, we can make this neighborhood better,” Robinson says. “When I bought my house, this was not a great neighborhood.”

The CNA opens its membership up to businesses and property owners, not just residents, and seeks a partnership relationship with developers, Robinson says.

“We wouldn’t want someone coming in and telling us what to do. We make a considerable effort not to tell people what to do,” he says. The group does, however, ask questions and makes its feelings known. It supported a special revitalization loan for the for example, to the point of going to see elected officials to voice support.

After Miller made initial inroads, more developers began eyeing the downtown-fringe neighborhood for its old buildings and inexpensive vacant land. Jack Matthews’ sweeping renovation of the massive Sears Roebuck & Co. Catalogue Merchandise Center, a portion of which dates back to 1913, brought media coverage and more interest to the area.

The 1.2 million-square-foot property, which spans a full city block, opened as South Side on Lamar in 2000 with 457 residential lofts, 25 artists’ lofts, and 120,000 square feet of office commercial and retail space.

“It was 17 acres close to downtown and was for sale at the time,” Matthews, the president of Matthews Southwest, recalls, explaining what initially attracted him to the property.

“That’s what got us originally looking at The Cedars. There are a bunch of things going on now, but if we look back 15 years ago — did we think it was going to develop faster? Yes, we probably did, but it just took the city a long time to accept that part of the city,” he says. “It takes a long time for perceptions to disappear, and the perception of ‘unsafe’ has now been replaced with the perception of ‘incredibly safe’ — a full change. The safest place is a busy place, and it just gets busier and busier, and at night that is now one of the busiest spots in town,” Matthews says.

PRIME LOCATION AND AVAILABLE PROPERTY

One of the neighborhood’s biggest drawing cards is its location on the southern edge of downtown Dallas. Because it doesn’t have any large corporate offices within its boundaries, the neighborhood has a much different feel from the central business district. The artists and entrepreneurs working in The Cedars, along with a growing residential base, give the neighborhood its own vibe.

Since developing South Side on Lamar, Matthews has also developed Alamo Drafthouse, Southside Flats, Gilley’s, The Cedars Social, the NYLO Hotel, The Beat Condominiums, and several restaurants, businesses, and taverns. He estimates that he’s invested about $200 million in the neighborhood.

He also owns the largest available contiguous tract of vacant land in the area — 60 acres — just west of the Alamo Drafthouse, an area he refers to as “The Rivers.” Development is on hold, awaiting a high-speed bullet train to come to the area.

Matthews, a director of the bullet-train entity Texas Central Partners, is one of 17 Texas family shareholders in the private high-speed rail project, which was endorsed by The Real Estate Council in January. He is also the developer of the transit-oriented development that is planned around three terminals: One in Houston, one outside of College Station, and one in Dallas. The Dallas site, just west of the Alamo Drafthouse, is expected to have a major impact on the growth of downtown Dallas and The Cedars. Preliminary plans call for office, residential, hotel, and retail space around the terminals.

RISING PRICES

Prices, while still affordable, are on the rise, and some of the area’s highly fragmented property owners seem more hesitant to sell as they wait to see if values continue to rise, says Scott Lake, urban land director at Davidson Bogel. He has worked extensively in The Cedars and understands its complexities.

Land sites, he says, are selling between the low $20s to the mid $30s per square foot with more than 100 acres of vacant, developable land in The Cedars. The area also has its fair share of dilapidated buildings for those who can imagine future uses. However, assigning a value to existing buildings in the neighborhood is a challenge as the quality varies widely, and the value is relative to the user, Scott Lake says.

INTEREST ON THE RISE

While Miller and Matthews were among the first to see potential in The Cedars, interest has been rising among a variety of local and international players, including an Australian developer, Australian Development Consortium, which envisions a six-story mixed-use development at 1601 Akard St.

“We’ve seen a lot of interest from developers,” Scott Lake says. “It’s my opinion that The Cedars has tremendous upside.”

Zad Roumaya, an entrepreneur, artist, and the owner of Buzz Works, has been in The Cedars for 18 years, bootstrapping incremental redevelopment projects while the area was still considered a fringe location. His first new construction project, The Buzz Lofts, was completed in 2007, and more recently he completed Digit 1919, a 102-unit apartment complex. He owns a total of seven properties in The Cedars.

“At any one time I’ve had seven to 10 personal guarantees in this district; that’s how committed I have been,” Roumaya says.

EcoView Homes, which has mostly developed in East Dallas until now, is one of the more recent entrants. It was attracted by price and downtown proximity, says Mike Smith, owner and manager of the eco-friendly builder, who says rising prices in East Dallas have made it challenging to keep price points under $400,000. EcoView bought two acres along Ervay about a year ago and is planning a condo development.

Jim Lake, known for his adaptive reuse of old urban buildings, says he first looked at the old 1915-era Ambassador Hotel — located on the eastern edge of The Cedars — more than three years ago. It was a reluctant tour, done at the insistence of his son, Scott Lake, who saw potential in the old structure — the city’s first suburban luxury hotel.

About a year after seeing the historic hotel, Jim Lake purchased it and is making plans to redevelop it into apartments with a restaurant and retail on the first floor, a speakeasy and co-working space in the basement and a rooftop bar. Construction is scheduled to begin in the first quarter of 2018. He’s also in talks with the city of Dallas about connecting the Ambassador property to the city’s adjacent park, Dallas Heritage Village, which includes historical structures from Dallas County.

LOCATION. LOCATION. LOCATION.

Jim Lake describes The Cedars’ best attribute this way: “Location. Location. Location. Literally right there on the southern tip of the Dallas downtown core.”

Just across from the Ambassador, Four Corners Brewery opened a retail taproom in mid-October. The microbrewery began brewing at the site in August after moving from smaller rented space in West Dallas that it had outgrown.

“We were looking for a place that we could purchase and own,” says co-founder Greg Leftwich. “We wanted to be as close to center of Dallas as possible from a cultural perspective and for tourism,” he says. “The Cedars was a natural fit for us because we saw the neighborhood as authentically diverse. There are a lot of artists, socioeconomic groups, and ethnic groups that are already embedded in the neighborhood and make the culture of The Cedars rich.”

“The good news about The Cedars is that there are a lot of existing structures that are ready to be used or repurposed,” Leftwich says. “I think the neighborhood was excited that we didn’t come in and just tear the property down and build something new.”

One of the two buildings on the site — the tap room — was built around 1915 and served as the horse stables and carriage house for the Ambassador Hotel, situated across the street.

‘IT’S NOT COOKIE-CUTTER STUFF’

Funky favorite Lee Harvey’s, owned by photographer Seth Smith, has achieved iconic status as a dive bar in a former pier-and-beam house on Gould Street. It was voted “Best Dive Bar” by the Dallas Observer in 2016. Homegrown businesses such as the coffee roasting studio and “listening studio” Full City Rooster contribute to the neighborhood’s distinctive flavor, as does Baby Back Shak, which has showcased Memphis-style barbecue for more than 21 years. The MAC Gallery, a nonprofit organization that advocates for creative freedom, moved into The Cedars in 2015 from McKinney Avenue.

One of the most exciting new developments in The Cedars is the Lorenzo, a hotel that is Larry Hamilton’s first project in the district. He also hopes to “juice up the entrance” to The Cedars with a 42-foot-high umbrella sculpture. Hamilton, founder and CEO of Hamilton Properties Corp., said the umbrella was inspired by another artistic vanguard for the neighborhood, the giant bowler hat sculpture by artist Keith Turman that sits atop a custom 20-foot-tall steel column overlooking Interstate 30.

“To be perfectly honest, its proximity to the convention center was more alluring than it being in The Cedars,” he says. Hamilton discovered that some hotel brands viewed The Cedars negatively and declined to be involved in the project. “We saw it positively, as an area that was coming of age — the next area of expansion.”

Jack Matthews says he understands why developers have fallen in love with the reinvigorated neighborhood, and he continues to invest there. “Even though prices have gone up, The Cedars is still the best buy in the city,” he says. “It’s an easy place to fall in love with. It’s not cookie-cutter stuff. It has its own character, which is unique and real. It attracts people who like something different.”

FROM STANLEY MARCUS TO JACK RUBY,

THE CEDARS HAS A HISTORY TO BEHOLD

The Cedars, named for the trees that once populated this area just south of downtown, is often called the city’s first neighborhood.

The neighborhood, which dates to the 1870s, began as a district of moderately priced homes, later becoming a favored location for Victorian mansions and cottages housing the city’s business entrepreneurs, Jewish population, and some of its wealthiest citizens.

The Cedars’ famous residents included Stanley Marcus, the founder of downtown luxury retailer Neiman Marcus and nightclub operator Jack Ruby, who shot and killed JFK assassin Lee Harvey Oswald. Ruby had several properties in The Cedars including a striptease bar, a theater, and a brothel. The former brothel — in a building that is now more than 100 years old — later was renovated into apartments and today houses condos.

The neighborhood’s wealthy eventually left for enclaves to the north and east, and The Cedars evolved into a heavy commercial and industrialized neighborhood. Most of its 19th-century homes didn’t survive the evolution and are gone now. Many of its old industrial buildings still stand, however, including the original Ford dealership building and the Southwestern Bell switching station.

“People moved out and you had that flight to the suburbs as things became industrial,” says Phillip Robinson, president of the Cedars Neighborhood Association. “It stayed that way right through the 1990s and into today there are still vestiges of the industrial era.”